Partitions of Poland—Policy Brief

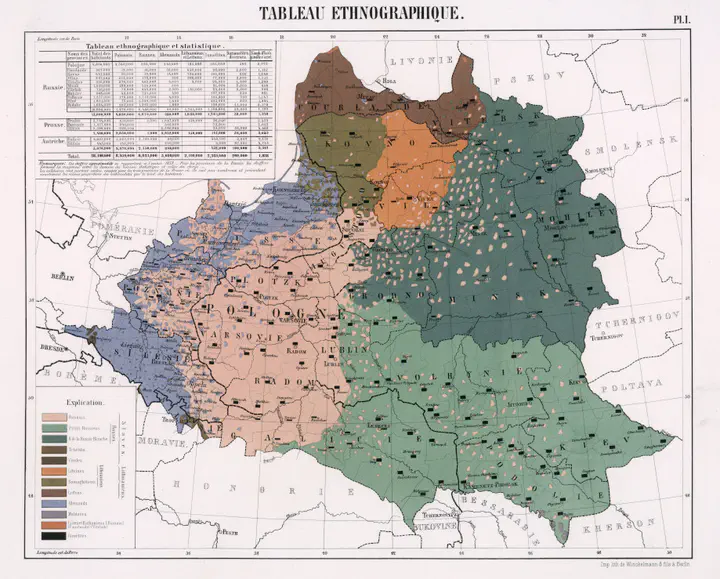

Poland in 1858

Poland in 1858

The Persistent Economically Significant Cultural Consequences of the Partitions of Poland, 1815-1918

Purpose:

At the end of the eighteenth century, the Kingdom of Prussia, the Russian Empire, and the Habsburg Monarchy divided the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth into three partitions. Historical evidence suggests no overlap of the borders with any pre-existing divisions or conditions.

Under the occupation, the cultures, institutions, and economies of the partitions diverged. Despite the reunification efforts by three subsequent regimes of the reborn Poland, literature finds persistent disparities in urbanization, income, education, religiosity, and political preferences across the former borders.

This study uniquely focuses on cultural differences of economic importance. By conducting an online survey targeted at a region with spatial discontinuity, it documents persistent effects of the Partitions of Poland between formerly Prussian and formerly Russian regions.

Key findings:

The Partitions of Poland Survey documents the persistence of small differences on a limited number of indicators. Consistent across several specifications, there are higher levels of membership and activity in social organizations in former Prussia (which confirms the conjecture of some sociologists). Historical narratives suggest that this effect may be a legacy of the 19th-century German-Polish cultural rivalry. There is also some empirical evidence for higher trust in schools, police, and courts; lower altruism; and more trust toward Russians relative to Germans in this partition.

Two results contrary to initial assumptions are that replacing location-based Prussian indicators with ancestry-based Prussian indicators weakens the results; and that higher age groups do not exhibit stronger treatment effects. These results suggest that vertical (or family-based) transmission is not the main channel of persistence of prosocial preferences.

The Partitions affect age, education, urbanization, and income groups differently, but no clear pattern of heterogeneity emerges across the outcomes. Rural areas drive strong positive effects of the Prussian partition on both income and activity in social organizations. However, I find no evidence that social organizations drive the income disparity there.

Contributions:

The Partitions of Poland Survey is the first survey targeted at the 1815 Prussian-Russian border. This contributes 3150 online interviews measuring economically significant beliefs, values, and preferences and documenting the localities where respondents and their ancestors to the level of great-grandparents lived.

The number of respondents allows me to rely on the narrow bandwidth of 15 kilometers rather than on geographic control variables that compensate larger bandwidths in other studies. The clarity of interpretation of this sharp RDD is a methodological improvement. In addition, ancestry data help understand migration patterns across the partitions and the role of vertical transmission.

To my knowledge, this is the first paper to establish a positive impact of the Partitions of Poland on social capital. This may be an example of how social mobilization against an occupier in the past can lead to persistently higher levels of social capital in the present. This study also suggests that vertical transmission does not necessarily suffice to explain the differences in prosocial preferences or behavior.

Research implications:

My results are consistent with Wysokińska’s (2017) findings that rural areas drive the income disparity and that the reason seems more related to levels of capital than to cultural differences. Future research could investigate the relationship between income and social capital across the partitions in rural Poland.

In addition, my paper supports Bukowski’s (2018) suggestion that the Partitions caused persistent differences in social norms toward schooling—I find a stronger belief in the objectivity of schools in former Prussia (for some of the demographics). The religiosity measures in my data lack statistical power but are in line with Grosfeld and Zhuravskaya (2014).

Policy implications:

Considering little historical evidence for institutional persistence and the newly-found weak statistical evidence for cultural persistence, there remain few possible explanations of the differences in social capital and income.

Thus, policy focus on building capital seems a reasonable implication for the former Russian partition of Poland. Forming social networks and increasing agricultural capacity are two examples of actions that make sense in the context of my findings and the existing literature. However, the exact cause of the inter-partition income disparity is yet to be empirically demonstrated.

You can find the full text of my thesis here. (Also hosted on Harvard Kennedy School’s website).